Redefining Transformation – New Challenge for All Leaders

How we think about transformation isn’t working anymore. The concept itself—and everything it stands for—runs the risk of joining a peer set of important sounding business buzzwords that have lost their meaning and impact along the way—like innovation, collaboration, and synergy. How leaders adapt and lead over the next decade must change.

To read more, see the below article which was published in the Spring 2017 issue of the People + Strategy Journal.

Redefining Transformation

By Dan Hawkins and Todd Fryling

How we think about transformation isn’t working anymore. The concept itself—and everything it stands for—runs the risk of joining a peer set of important sounding business buzzwords that have lost their meaning and impact along the way—like innovation, collaboration, and synergy.

Lifespans of successful companies continue to shrink. Is it because companies don’t transform or don’t evolve? Considering its continued popularity, there are many elements around the idea of transformation that need to change. Our traditional approaches to transformation need to adapt to the VUCA (volatile, uncertain, complex, ambiguous) environment that we now live in. Everybody has seen some version of those adoption curves showing the exponentially shrinking timeframes for user adoption of telephones, televisions, computers, and Facebook. Companies lose relevancy faster than you can say Blockbuster Video.

Given that context, what does business transformation look like in today’s world? Upon mentioning the word “transformation,” several things pop in your head. It’s big, it’s difficult, it’s meaty, and it’s all encompassing. It’s also long, complex, disruptive, and very risky. More concerning, it gives the impression that there is a beginning and an end to the change. One of the benefits of the reactionary nature of most transformation efforts is the “burning platform” it provides you. It justifies the initiative. It cuts through the noise to rally and motivate the troops. For some companies, this works well. For example, at a very successful technology company where we had led a series of senior leadership development programs, one of the themes from multiple cohorts of vice presidents was a recognition that they worked at their best—as one team with no silos—during times of crises, whether due to losing a major client or dealing with a systemic software outage. However, once the crisis was resolved, old and less productive behaviors crept back into the system.

The question among the senior leaders always becomes, how do you keep people’s attention when the crisis or initiative goes away? When we think of business transformation, one of the biggest changes we need to make is in its framing. In many respects, declaring the need for business transformation is already a confession that you’re too late—you’re reacting, you’re on your back foot. The traditional framing of business transformation works in relatively stable and predictable environments; however, these types of environments are now more the exception than the rule.

In her 2013 Harvard Business Review article1 , Rita Gunther McGrath argues companies need to rethink how they formulate strategy in the new world order, where sustainable competitive advantages have given way to transient advantages with shelf-lives that can be measured in months instead of years. A similar rethinking needs to happen with how we approach business transformation. Based on McGrath’s research, companies that successfully engage in developing more agile, transient strategies rarely engage in traditional transformation efforts, such as major restructurings, downsizings, or large reductions in force. They focus on evolution; small-scale changes aimed at ensuring relevance rather than big swings at the plate. Many of our multinational clients have abandoned their sacred 5-year strategic planning processes and reviews due to constant change in the global marketplace. Strategic plans often become obsolete or irrelevant in six months. These corporations have replaced these plans with annual strategy refreshes, “which take into account recent environmental changes and near-term outlooks. The strategic aspirations and vision may not change; however, where and how they place their bets could. Strategy has evolved from a corporate process to a series of ongoing conversations and decisions.”

Organization Change Is Growing Up

Prevailing models for the successful implementation of organizational change have themselves been the subject of intense transformation and revision for the past several decades. As one of the earliest models of organizational change, Kurt Lewin’s Unfreeze-Change-Refreeze model separated the change process into three distinct phases. Following Lewin’s seminal work, other models of organizational change were proposed in the ensuing decades, such as William Bridges’ three stages of transitions. Much like Lewin’s model, however, subsequent descriptions of change only sought to organize the process of transition, rather than integrate organizational change with strategic goals or incorporate change as a continuous aspect of business operations.

Amidst the trends of restructuring and downsizing and the rapid proliferation of technology in the 1990s, business leaders recognized a great need to implement organizational change that could proactively confront the challenges of a global business climate in the throes of extreme transformation. Answering the call to better understand change management, John Kotter’s foundational article and book Leading Change sought to sketch how, in eight steps, business leaders can successfully enact an organizational change initiative. By the end of the 1990s the phrase “change management” had become commonplace in both the boardroom and the C-suite.

While change management during the 20th century required leaders to describe the various states of transition to act and ensure successful outcomes, the 21st century brought a new quandary to the forefront: How can change management be integrated throughout all business functions, capabilities, and environmental factors? We think this is where “transformation” evolved. Company leaders recognized that managing change was no longer sufficient given a myriad of external, uncontrollable factors; therefore, transformation was born. It sounds bolder, broader, and more urgent.

Like strategy, our models for how we think about change also must evolve. All of this comes back to the question raised by that group of technology vice presidents we mentioned earlier: how do you practice and sustain the right behaviors without the crisis or initiative? Without the burning platform typically associated with business transformation? To have the greatest impact and relevancy in today’s VUCA world, transformation must be a mindset, a collection of behaviors, and a shared responsibility. It’s not a logo, a war-room, or a vision statement. It cannot be solely reactive—it must also be proactive. It must sustain itself beyond the initial burning platform.

It’s About Behaviors Not Initiatives

For transformation to be successful and sustainable, the focus must be on behaviors—everyday practices that transcend the formal artifacts of traditional transformation efforts. One industrial manufacturer we work with was trying to transform from a cyclical capital goods company to a services business to create a more recurring, profitable revenue stream. The strategy and key initiatives were sound; however, traction was not achieved until the leaders changed their language and everyday actions. The long tenured organization did not mobilize until everyday behaviors shifted at the top. Examples of this included recognizing services as a legitimate business, promoting top talent into the services business, challenging the current business model, and demonstrating flexibility to adapt to a new set of customer expectations.

While companies are learning to become more focused on how they transform and less on what to transform, we continuously observe a few critical capabilities that drive and sustain transformation in a VUCA world.

Curiosity

Companies that have embedded transformation into their DNA are naturally curious. Uber and Airbnb’s transformative impact on the transportation and hospitality industries, respectively, likely started out with several “Why” and “What if” questions. This curiosity must extend beyond the confines of one’s role, function, or industry. Transformation happens at the adjacencies, in the spaces in between. Successful startups find their first (and potentially “transient”) point of differentiation here.

For a more mature enterprise, the true test of curiosity comes when the capability is not only focused on the market or on the competition, but when the “why” and “what if” questions are addressed internally. To ensure more open communications and idea sharing, one technology client eliminated monthly executive team meetings designed to review financials, initiative progress, and typical management information sharing with standard agenda items. Instead they adopted a monthly “Think Day” where all executive leaders arrive to the board room without a set agenda. Each leader comes with one or two topics they would like to discuss and debate. Leadership team members look forward to these meetings now as opportunities to “spar” on new ideas rather than rehash last month’s results.

Agility

Related to curiosity is an organization’s capability to quickly and efficiently change direction when needed based on consumer, competitive, or market insights. Several articles touch on agility as a key organizational competence. The absence of agility is at the essence of Clayton Christensen’s book The Innovator’s Dilemma. It’s what keeps companies from siphoning resources from their cash cow to fund the next disruption.

As McGrath shares in her article on transient strategy, companies must be bold and courageous about what they choose to discontinue and avoid being trapped into thinking they can exploit current successes in perpetuity. Pick up the iPhone 7 and you’ll know what I’m talking about. To us, agility is equal parts learning and acting based on that learning. Learning without action is just academic. Action without learning is just churn. The reality of successfully operating in today’s environment is that there will be bumps along the way. Consider Netflix’s decision to change its subscription model when streaming began overtaking DVD rentals. Customers reacted swiftly, showing their disapproval with their feet. The broader lesson, however, isn’t Netflix’s mistake, but rather its responsiveness in reconfiguring the model.

Discipline

This is one capability where more mature enterprises may have the advantage so long as discipline isn’t confused with dogma. Without discipline, curiosity and agility cannot get the job done. Transformative leaders create effective tension between operational and innovative forces. Discipline reflects how you channel your curiosity and agility. Do you have rigorous, repeatable processes and systems in place to assess your external environment, competitors, and customers? Do you have methods to holistically measure your own organizational health, strengths, and weaknesses? Do you take a structured approach to how you experiment and test hypotheses—whether it’s with a new product or compensation program? Do you have specific practices to capture and act on learnings? Are you clear on how and who makes what decisions?

It should come as no surprise that what makes the frameworks like agile software development or design thinking work is not how revolutionary their concepts are, but rather the discipline in which they are carried out. Many of the concepts are quite simple, but they require discipline. Ask a practitioner of Covey’s Four Disciplines which part of transformation is the hardest to embed. Not surprisingly, it’s discipline. One company that we’ve worked with who has adapted the agile methodology referenced above has successfully implemented the 15-minute daily scrum meetings. These serve as the equivalent of discipline adrenaline shots to keep things moving. They are sacred—missing them is not an option. Discipline is also a critical, albeit overlooked component of change management. In working with a consumer packaged goods company who had acquired another company, the management team committed and followed through with providing weekly updates to the organization. Some weeks had big news, others, very little, but no week was missed.

Assessing Organization Readiness

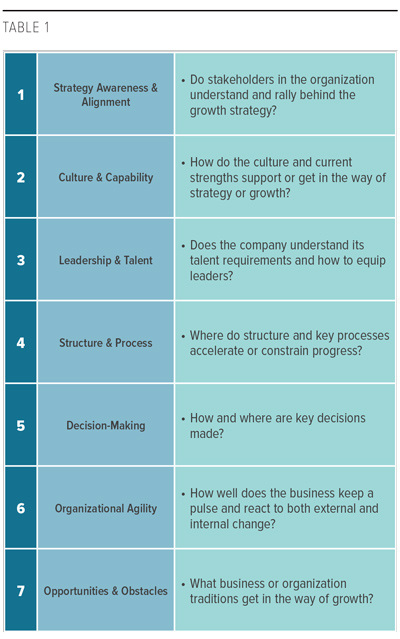

As mentioned above, transformation is less about a beginning and an end, abandoning what once made you successful, or becoming a completely different enterprise. There is no beginning and end. It is comprehensive and ongoing and should be considered an evolutionary approach to adapting to external volatility and unpredictability. The key is organization alignment: determining how and when to adapt different organization levers to ensure that all levers are working toward the same outcome. The goal is more about acceleration than transformation. We often work with companies to assess their organization alignment and readiness in seven areas to transform (or better yet, advance) themselves (see Table 1).

As mentioned above, transformation is less about a beginning and an end, abandoning what once made you successful, or becoming a completely different enterprise. There is no beginning and end. It is comprehensive and ongoing and should be considered an evolutionary approach to adapting to external volatility and unpredictability. The key is organization alignment: determining how and when to adapt different organization levers to ensure that all levers are working toward the same outcome. The goal is more about acceleration than transformation. We often work with companies to assess their organization alignment and readiness in seven areas to transform (or better yet, advance) themselves (see Table 1).

In addition to understanding market dynamics, having clarity around business differentiators, and developing a solid yet adaptable strategy, corporate executives must ensure these organization accelerators are aligned for success. It is critical to have an honest calibration with both quantitative and qualitative evidence. Due to never-ending change in markets, talent, and technology, no company is ever 100 percent aligned, providing the basis for constant evolution over dramatic transformation. Business leaders should know the strengths and constraints for each and always have a roadmap to advance forward.

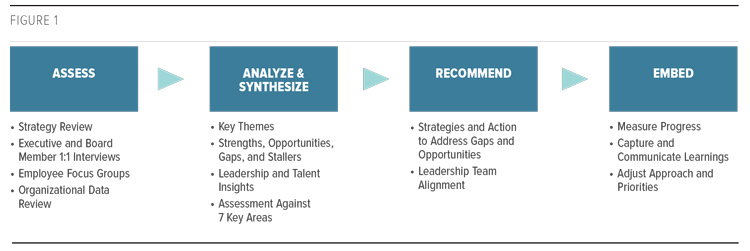

We have a retail client that is growing at a torrid pace, expected to double its business and stores over the next three years. Despite their past success, there were concerns about their ability to keep up the pace and whether they have the leadership and organization capacity to grow two times their size. They are not trying to “transform” because their success formula works. The company leaders, however, do recognize that they must “evolve,” beginning with a comprehensive yet candid organization diagnostic. After a series of strategy and organization reviews, key leader interviews, critical talent focus sessions, brief alignment survey, and digging deep into their business operations, we provided a balanced view on organization strengths and constraints related to their ambitious growth strategy.

Specifically, they need to flatten their organizational structure, push down decision-making authority, build the leadership pipeline, improve their capability to assimilate external leaders and better align the executive team around how they spend their time together. Taken individually, these actions are not revolutionary; however, they all share interdependencies with one another so that when tackled together, their collective impact is transformative. This is not an organization transformation but more of a realignment or adaptation. The overall organization diagnostic process is outlined in Figure 1 above.

Role of the Leader Redefining transformation places new demands on CEOs and CHROs. Traditional change leadership models require communicating an end-state, creating urgency, focusing on logical steps and initiatives, engaging employees, and recognizing successes. These components are very important to leading change transformation in a predictable environment or driving a change initiative. However, viewing transformation as more evolutionary, adaptive, and focused on advancing an organization reveals different actions that must be taken by an organization’s leaders. Leaders must adopt and role model the following:

- Champion evolution over revolution. There is no benefit from deprecating the past and focusing on the destination of a single definitive future. Vision statements have a role, but leaders need to spend more time on how the organization must evolve not transform. Focus on the pivots. Evolving builds on past success and adaptations and thriving amidst unknown challenges. We doubt Darwin would have been renowned for a “theory of transformation.” Jeff Bezos is a great example of how a leader can evolve a successful business model from selling books over the internet to an online commerce leader for virtually anything. Bezos often talks about he constantly evolved his company (and himself) since founding Amazon many years ago, despite being wildly successful.

- Challenge the organization to rethink assumptions and paradigms. Naturally, highly successful organizations are proud and confident. Top leaders must encourage fluid, innovative thinking about unexpected market changes, untraditional competitors and new solutions that seem counter to the business model. While Pepsi has always been a dominant player in the soda and snack food industry, Indra Nooyi challenged her leaders and tenured organization to enter the health-foods market. No one saw this coming, and Pepsi is now a leader in the world’s migration toward healthier living.

- Prime the pump between operational and innovative constituencies. Too many companies believe innovation and discipline are mutually exclusive. As stated earlier, we believe a great strategic plan requires creativity and execution. Business leaders should encourage both innovation and operational leaders to challenge each other without declaring winners. Upon taking over the helm at industrial powerhouse Ingersoll Rand, Mike Lamach recognized the need to elevate innovation and technology in this traditional manufacturing centric company. He quickly hired a first ever EVP of Innovation and launched a significant lean deployment initiative across the company at nearly the same time. These seemingly competing efforts found a way to coexist and enable each other’s success amazingly well.

- Identify and advance organization capabilities. Leaders must identify and develop the expertise, culture, leadership, and organization that will differentiate in the market regardless of past successes. All too often companies and business leaders develop elaborate strategies without discussing organizational implications. As strategic plans become more fluid, leaders must also view their organizations as always in a state of change regardless of their success. They should have the insight and courage to change-out leaders, adjust decision-making traditions, realign a sacred organization, or hire strategic talent to integrate new thinking and competencies. Despite recently achieving #1 in its market, a life sciences client CEO recognized the need to serve the market differently in the future by creating a more seamless one face to the customer to an increasing more sophisticated market. He boldly decided to collapse several long established, successful business units into a singular commercial organization.

Our Challenge for CHROs

In addition to becoming an effective strategic partner with the CEO driving the above capabilities across the company, the CHRO needs to ensure her own house is order. HR functional capabilities must evolve faster than any function or the company’s organization capabilities and business could be at risk in the future. Human capital is often listed as the No. 1 constraint to business growth by CEOs today. Businesses are demanding more from the HR function. Consider these startling findings:

- According to a recent study by the Hackett Group (2015), most HR organizations are underprepared to address their enterprise’s most critical strategies and goals.

- APQC Talent Trends reports that there will be a leadership and talent shortage in 2020 due to lack of human capital and HR strategy in most companies (2015).

- McKinsey and the Conference Board recently reported that CEOs worldwide see human capital as a top challenge, yet rank HR as the eighth most important function in the company (2016).

Heads of HR are encouraged to look at their HR organization to determine how aligned their talent, structure, priorities and initiatives are aligned with a rapidly evolving business. Our point of view on transformation requires more flexibility and agility in everything within the HR function. CHROs must consider realigning long standing programs such as five-year performance share equity plans, employee engagement approaches, traditional college recruiting, career development, and leadership development programs with a greater focus on responsiveness to the changing world we live and work in.

Leadership models have not evolved in a couple decades, yet the internal and external challenges leaders face have changed significantly. Leaders are being trained and developed for predictable challenges and current corporate initiatives to lead a stable workforce representative of the year 2000, not 2025. Over the last couple years, we have seen a surge in requests to help assess, coach and develop leaders for volatile and uncertain times. Well-trained, pedigree leaders are becoming ill-prepared and struggling in unpredictable economic environments.

Investing in leadership effectiveness is not new. However, improving leadership impact in a VUCA world is. CHROs must challenge traditional approaches to preparing leaders for the future. This is one example of how the head of HR should rethink how and where their HR functional priorities and capabilities are enabling the future uncertainties and how businesses must evolve.

Final Thoughts

For leaders, further down the organization, there’s a dirty little secret around how to lead through transformations. Focus on the leadership fundamentals. As part of their ongoing focus on business transformation, McKinsey identified 24 actions associated with successful business transformation in their 2015 McKinsey Quarterly article, How to beat the transformation odds2. The more of these actions you take, the greater probability that your transformation effort meets or exceeds its goals. To be clear, it’s a great list of actions. Things such as “everyone can see how his or her work relates to the organization’s vision” or “the organization develops its people so that they can surpass expectations for performance.” However, if we didn’t know we were reading an article on business transformation, we would have just thought that these represent solid, everyday leadership practices. To be fair, some were transformation initiative specific, including “Leaders used a consistent change story to align organization around the transformation’s goals,” but again, substitute “transformation” with “business,” and you are back to the benefits of great leadership.

There is no doubt that transformation will continue to be a platform for many years to come. Given the exodus of retiring baby boomers over the next five years, we will see an unprecedented number of CEO transitions across large corporations. Incoming CEOs will more often be first timers in the big seat, and therefore will be compelled to make their mark by transforming their newly inherited organizations. Heraclitus once said, “Change is the only constant in life.” The change that corporations will face will be market, political, economic, global, and technological. These dynamics are volatile and, in many respects, unknown. (Who reading this predicted a Trump presidency, Brexit, self-driven taxis, or a Google phone just two years ago?)

Business transformation often has a burning platform and clear path to an end-state. This type of change tends to work for initiatives and programs yet falters in strategy when so many unknown factors arise during the strategic horizon. Another client, a successful industrial supply distributor, historically developed business plans around GDP growth expectations, industrial expansion, commodity trends and traditional competitive movements by other industrial distributors. Never in their remotest thoughts did they expect Amazon to become a formidable competitor.

Time to transform? No, rather it’s time to adapt and respond by getting into the digital and analytics age. Leaders should stop yelling “transformation” from the top of the mountain. It’s time to consider evolving the organization instead.

Dan Hawkins is president of Summit Leadership Partners, which he founded after 25 years in the corporate world as CHRO and chief talent officer with several successful global corporations. He can be reached at dan.hawkins@summitleadership.com.

Todd Fryling, Ph.D., is a principal at Summit Leadership Partners and has more than two decades of experience in leadership and organization development. He can be reached at todd.fryling@ summitleadership.com

References

1 McGrath, R. G. (June 2013). Transient advantage. Harvard Business Review. 91.6.

2 Jacquemont, D., Maor, D., & Reich, A. (April 2015). How to beat the transformation odds. McKinsey Quarterly. Available online at https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/ our-insights/how-to-beat-the-transformation-odds.